As the pandemic has progressed, collective minds have shifted their focus from the direct mortality impacts of Covid-19 to the longer-term implications. One of the defining features of the pandemic over the longer term will be the toll on the economy. We know from experience of economic contractions that there will be knock-on effects on the health of the population. Kenny McIvor writes

Recession

The UK economy fell by 9.9% in GDP terms over 2020 having experienced its first recession in 11 years, with GDP down by 2.9% in Q1 and a record 19.0% in Q2 as a result of the pandemic and the ensuing lockdown. Although the figures started to bounce back in the later part of the year after this initial shock, with a 16.1% increase in Q3 and a 1.0% increase in Q4, the UK still experienced the largest annual fall in GDP on record (ONS, 2021).

Access deeper industry intelligence

Experience unmatched clarity with a single platform that combines unique data, AI, and human expertise.

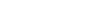

Table 1 shows the UK’s experience over the three most recent recessions: the global financial crisis (or Great Recession) and the recessions of the 90s and 80s. The Great Slump (the UK fallout from the Great Depression of the 1930s) is also shown, as a more severe event, for comparison purposes. Information to date indicates that the impact emerging from the pandemic will be shorter and sharper than anything the UK has experienced before. What will be the mortality impacts of this recession after the pandemic?

While this article gives thought to the exceptional circumstances arising from lockdown and social distancing, these have not been explicitly allowed for in any of this analysis. Likewise, great uncertainty relates to the extent of government policy changes – recession implies a ‘default option’ of reduced health expenditure, but policy changes might lead to the opposite (at least in the short term – in the longer term, economic reality is harder to avoid).

US Tariffs are shifting - will you react or anticipate?

Don’t let policy changes catch you off guard. Stay proactive with real-time data and expert analysis.

By GlobalDataWhat might economic damage mean for life expectancy? While the relationship between mortality and economic status is unquestionable in the long term (on average, the richest economies have the highest life expectancies), in the context of economic cycles the relationship is a surprising hotly debated topic.

A prevailing argument is that mortality rates rise when the economy declines because unemployment and government austerity lead to a general worsening in health and healthcare. The counterargument is that recessions lead to behavioural changes and reductions in environmental pollution, motor accidents and occupational risks – and these lead to mortality rates falling. Both arguments have merit.

Drivers and their pandemic pathways to mortality impacts

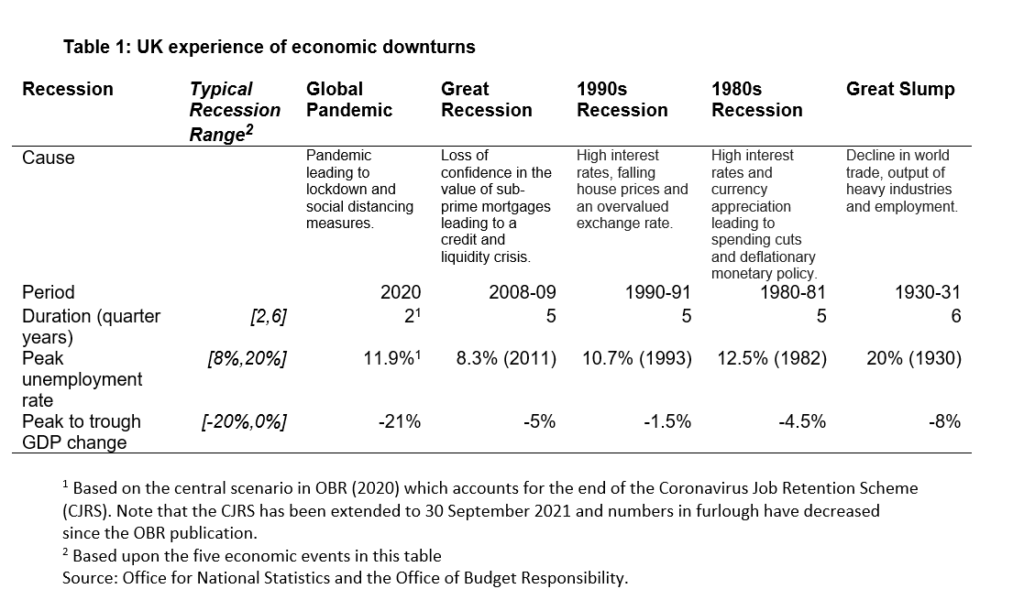

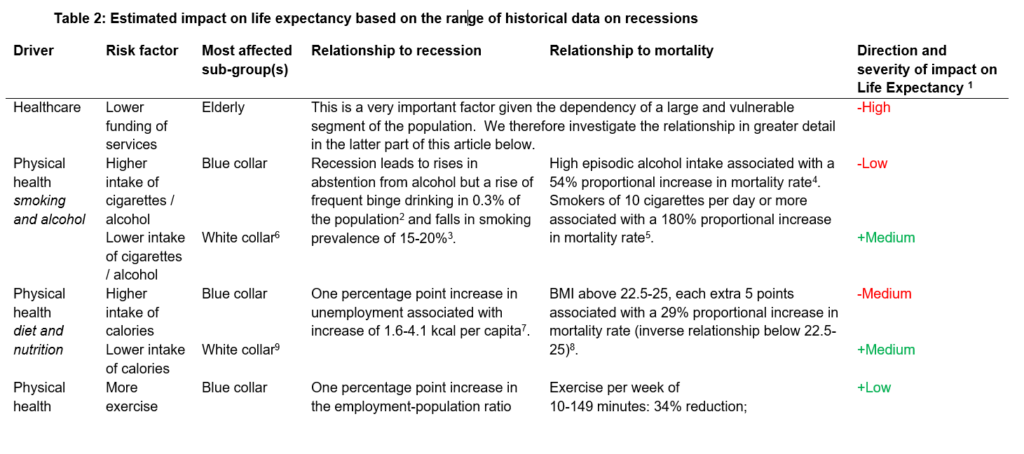

The NHS is at the forefront of the fight against amenable deaths (deaths that are preventable given timely healthcare) but is highly dependent on public spending. Due to the effects of improved healthcare being felt across a wide range of ages, there is a broad scope of dependants, such as the working age population, those prone to chronic health conditions as a result of recession, or those in care homes who are highly susceptible to declines in availability or quality of medical care.

This point may be further accentuated given that the lockdowns have already put the NHS ‘on the backfoot’ as a result of curtailments of treatment, postponement of non-urgent surgeries and reductions in intensive care unit capacity (although much improved at time of writing).

Some element of the resulting impact of recession also comes down to how individuals have chosen to cope; there are several modifiable health behaviours that play a role. Alcohol consumption has been shown to rise among those made unemployed, but drop at an overall level, perhaps due to tighter budgets. Smoking behaviour is not so clear, but rises have been observed among those made jobless, particularly in lower socio-economic groups. Diet and nutrition appear to vary by geography, perhaps due to cultural differences in cooking and cuisine, but there is a tendency in developed Western countries to see higher calorie intake during recession.

The psychological impacts of recession also have a negative effect. A rise in suicide rates is observed during recession and the rises are often greatest among young working-age males. We could well see a ‘perfect storm’ of negative mental health factors arising from social isolation, financial anxiety and job uncertainty.

For each driver, Table 2 provides a potential impact (author’s own estimate) based on the range of historical data on recessions as measured on the metrics provided. The impact is summarised as low, medium or high, where low impact indicates that the impact may be fewer than 100 deaths per year during the recession, medium impact up to 1,000 deaths, and high impact greater than 1,000 deaths.

Overall adverse outcomes are expected in the longer term for the elderly and for younger lives in the short term. The negative effects are also weighted more towards blue-collar workers, while white-collar workers see more beneficial effects emerge.

Indeed, subsequent research has revealed that, whilst there is variation among the effects of healthcare expenditure across high and low socio-economic sub-populations, the least deprived sub-populations experience mortality improvements around 40% higher than those in the most deprived decile.

Healthcare funding versus outcomes

Analysis shows that for every 1% of additional funding received by the NHS, there has been a corresponding 0.4% increase in mortality improvements. If this relationship were to hold, a fall in GDP of 20% passed on directly in lower NHS funding would therefore see mortality improvements cumulatively 8% lower than they would have otherwise been over the next 10-year period as a result of the economic impact of the recession. Equivalently, under this scenario and assumption, mortality improvements would be 0.8% p.a. lower for 10 years, which equates approximately to a one-year shortening of life expectancy at age 65.

Such effects may be mitigated by government policy changes; on the other hand, there are practical limits as to how much the laws of economics can be manipulated. It is also likely that a high proportion of any increase in health expenditure would be passed on to staff via salary increases, given the public mood of gratitude to the efforts of often low-paid healthcare workers.

Summary

There is a complex relationship between economic performance and health risk factors, and what holds true for one gender, age bracket or social group may not be true for another. We may find that the above relationships vary from country to country, or that the upcoming recession produces results that are different from the recessionary effects of the past.

By the same token, there is evidence that economic recession can have a positive impact on health. In subsequent research on the UK Income Protection insurance market, data has been found that indicates that a decrease in GDP positively correlates with an decrease in mental health claims the following year (although this also correlated with a decrease in recoveries), suggesting that a healthier economy does not necessarily lead to a mentally healthier population.

Additionally, the particular circumstances of the Covid-19 pandemic are likely to exacerbate the recession’s impact on health. Factors at play include potential accelerated obesity (ie the ‘Covid stone’), disproportionate youth unemployment and other longer-term behavioural changes, such as increased social isolation, particularly among the vulnerable.

Covid-19’s direct short-term mortality impacts is disproportionately on the elderly and infirm after the pandemic. Research suggests that the longer-term impacts will bear down on this group further and be disproportionately severe upon the poor, who rely most heavily on the nation’s health service.

Kenny McIvor is the director, insurance consulting and technology, at Willis Towers Watson.